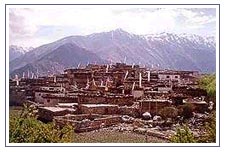

Landlocked

behind formidable mountain barriers in the western Himalayas, sheltered from

the rain-bearing monsoon winds, the remote and desolate district of

Lahaul-Spiti in Himachal is renowned not only for some of the wild, untamed

and enchanting mountain scapes but also for its unique Buddhist culture.

Covering a total area of over 12,000-sq-kms, Lahaul-Spiti is the largest

district of Himachal Pradesh. It shares a common border with Tibet in the

east. A lofty offshoot of the great Himalayan range in the southeast

separates it from Kinnaur. In the north, the Baralacha range separates it

from the cold desert of Ladakh, while the Chamba and Kullu district lie to

the west respectively.

Lahaul's only link to the outside world is by a road, which runs over

the 3,980 m high Rohtang Pass. Lahaul is separated from Spiti by a high

mountain range running towards the north from the great Himalayan range. A

treacherous road over the Kunzam Pass connects the two valleys. Another road

from Kinnaur links Spiti to the Hindustan-Tibet road.

Withstanding The Harsh Environ

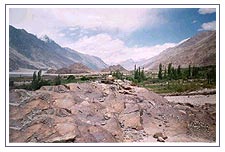

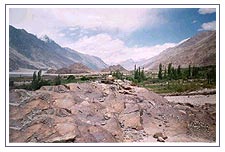

Enmeshed in the folds of the great

Himalayas, the climate is cold and arid, with very little rainfall. The

topography, therefore, consists of dry, dusty desolate mountains, virtually

devoid of vegetation spread endlessly in all directions like a moonscape,

resembling Ladakh and Tibet. The monotony of this stark, haunting russet

landscape is broken only by shades of green along the cultivated river

valley.

Sculpted by the wind and moulded alternately by freezing cold and searing

heat, the landscape of this frontier district has evolved a distinctive

profile. Steep towering cliffs of hard rocks rise up into the perpetual

azure sky all around, their slopes covered with heaps of weathered rocks. At

the centre, the rivers have played their part, cutting deeper and deeper

creating fertile banks. Few parts of the Himalayas can compare with Lahaul

Spiti for sheer grandeur. And splendour of the mountains, for here nature

holds sway in its wildest and grandest manner.

Bearers Of A Historic Cultural Heritage

Marked

by high mountains, bleak rugged topography and a harsh climate, the cultural

landscape of this Himalayan borderland is characterised by a unique blend of

two adjacent cultures. The Sino-Tibetan in the north and the Indian culture

in the 7th century AD and with the passage of time it became the major

religion of Lahaul-Spiti.

Today the district is studded with numerous Buddhist temples and

monasteries including Labarang, Gondhala, Dalung, Keylong, Guru-Ganthal,

Darcha, Markula in Lahul and Dhankar, Mud, Lidang, Rangrik, Ki (also spelt

as Kye), Losar and Tabo in Spiti. A millennium old Tabo is one of the area's

most revered monasteries. Often called the "Ajanta of the Himalaya"

because of its breathtaking murals and stucco images, tabo's sanctity

in trans-himalayan buddhism is next only to tibet's tholing gompa.

Apart from their religious influence the monasteries are also strongholds

of tradition and treasuries of the region's art and manuscripts.

Gompas, forts and chorten scattered all over the vastness of this cold

desert provide an unending feast for the sightseer and for scholars, some

authentic foot-notes and references to the local history and culture.

The Lahaul district of Himachal is one rare pocket in the Indian Himalayas

where one may trace a continuous course of development of Trans-Himalayan

Buddhism and it is probably one of the last remaining areas in which the

original Tibetan-Buddhist culture remains untouched either by communism as

in tibet, or by the dissolving influence of tourism to which ladakh has been

exposed.

The

traditional economy of this tribal belt was based on agriculture, sheep

rearing and trade. The subsistence economy and culture evolved in response

to the hostile environment. However with massive developmental works such as

road construction, modern agriculture and horticulture, Government services

alongwith the presence of a large number of "outsiders", armed

forces, traders, government servants and road workers has altered the

traditional way of life.

Changes have occurred in dress patterns, food habits; traditional

occupations like sheep rearing and even in the religious life. Although

change is inevitable and no community wishes to preserve itself as a museum

of backwardness, it is the rapid pace of change and a lack of understanding

of the nature of change, which a society is unable to control, or direct

that touches a cord of concern. The development of tourism accelerates this

process of change and rapidly pushes traditional societies into the global

economy totally ill-equipped.

Promoting Tourism

Ladakh

was opened to tourism in the early 1970s without making any adequate

preparation and ensuring safeguards. Since then, uncontrolled tourism has

transformed Ladakh from a traditional to a typical tourist destination and

many see western culture swamping the Ladakhi way of life. Today, the

self-sufficient Ladakhi economy has undergone a massive and dramatic shift

to one, which is dependent on the outside.

However, unlike Ladakh where uncontrolled tourism has disturbed the

delicate ecological balance and brought drastic socio-cultural changes,

Lahaul-Spiti is yet to face the full force of tourism. Tourism, if

successfully managed, can contribute to the ability of the tribal people of

this district to control and direct the change they are undergoing. Tourism

development, poverty alleviation, awareness generation and strengthen the

self-sufficient economy. This is the key to turning tourism's impacts

from a burden into lasting sources of benefit. Isolated for centuries due to

the inaccessible terrain and inhospitable climate this region is fragile,

hence adequate safeguards need to be taken to protect this tribal belt from

the adverse influence of tourism.

Such fragile areas should be open only to a very limited number of high

spending tourists with proper regulatory control as is being done by Bhutan.

Inspite of the large foreign exchange earnings that tourism brings, the

Bhutanese government has been far-sighted enough to consider the hidden cost

of tourism to its environment and culture by strictly controlling the number

and the movement of tourists in the country. With only two entry points into

the district, the government can easily restrict the number of tourists to

the carrying capacity of the fragile environment. This, of course, is not a

very fashionable decision to take but it does place the interest of the

local people and their environment before short-term and cost-laden profits.

Tourism is only commencing in Lahaul-Spiti. The government therefore needs

to finely tune the tourism industry to the local culture and the

environment. The vulnerable nature of tourism to unstable political, social

and economic conditions and seasonal nature of tourism dominant in the

mountains should be overcome by efficiently planning the tourism

infrastructure to make it multifunctional.

In fact tourism development must be integrated with the overall development

of the region and the local people should be invited to participate in

tourism right from the planning stage. It is also necessary to ensure some

incentives to the locals from tourism. Environmental considerations must be

integral in development of tourism in this region. Great care needs to be

exercised to conserve the local culture, which is its greatest asset.

By planning and promoting a healthy, sustainable, tourism industry in this

cold desert district, the government will have fulfilled its share of

responsibility but in the end, it may not be the number of tourists but

their sensitivity towards the local culture and environment that will

determine the complexion of tourism and the future of this unique heritage.

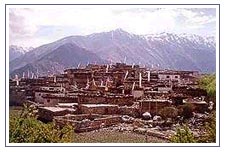

Landlocked

behind formidable mountain barriers in the western Himalayas, sheltered from

the rain-bearing monsoon winds, the remote and desolate district of

Lahaul-Spiti in Himachal is renowned not only for some of the wild, untamed

and enchanting mountain scapes but also for its unique Buddhist culture.

Landlocked

behind formidable mountain barriers in the western Himalayas, sheltered from

the rain-bearing monsoon winds, the remote and desolate district of

Lahaul-Spiti in Himachal is renowned not only for some of the wild, untamed

and enchanting mountain scapes but also for its unique Buddhist culture. Marked

by high mountains, bleak rugged topography and a harsh climate, the cultural

landscape of this Himalayan borderland is characterised by a unique blend of

two adjacent cultures. The Sino-Tibetan in the north and the Indian culture

in the 7th century AD and with the passage of time it became the major

religion of Lahaul-Spiti.

Marked

by high mountains, bleak rugged topography and a harsh climate, the cultural

landscape of this Himalayan borderland is characterised by a unique blend of

two adjacent cultures. The Sino-Tibetan in the north and the Indian culture

in the 7th century AD and with the passage of time it became the major

religion of Lahaul-Spiti.  Ladakh

was opened to tourism in the early 1970s without making any adequate

preparation and ensuring safeguards. Since then, uncontrolled tourism has

transformed Ladakh from a traditional to a typical tourist destination and

many see western culture swamping the Ladakhi way of life. Today, the

self-sufficient Ladakhi economy has undergone a massive and dramatic shift

to one, which is dependent on the outside.

Ladakh

was opened to tourism in the early 1970s without making any adequate

preparation and ensuring safeguards. Since then, uncontrolled tourism has

transformed Ladakh from a traditional to a typical tourist destination and

many see western culture swamping the Ladakhi way of life. Today, the

self-sufficient Ladakhi economy has undergone a massive and dramatic shift

to one, which is dependent on the outside.