The Himalayas is one of the youngest mountain ranges in the world. Its

revolution can be traced to the Jurassic Era (80 million years ago) when the

world's landmasses were split into two: Laurasia in the Northern

hemisphere, and Gondwanaland in the southern hemisphere. The landmass which

is now India broke away from Gondwanaland and floated across the earth's

surface until it collided with asia. The hard volcanic rocks of India were

thrust against the soft sedimentary crust of Asia, creating the highest

mountain range in the world.

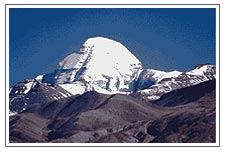

It

was a collision that formed mountain ranges right across asia, including the

karakoram, the pamirs, the Hindukush, the Tien Shan and the Kun Lun. The

Himalayan mountains, at the front of this continental collision, are still

being formed, rising and assuming complex profiles. For the ancient

geographer, the complexities of this vast mountain range were a constant

source of speculation. From the earliest accounts, Mt. Kailash was believed

to be the centre of the universe with the River systems of the Indus, the

Brahmaputra, and the Sutlej all flowing from its snowy ridges and

maintaining the courses which they had followed prior to the forming of the

Himalaya.

The Sutlej was able to maintain its course flowing directly from Tibet

through the main Himalayan mountain range to the Indian subcontinent, while the huge

gorges on both flanks of the Himalaya reflect the ability of the Indus and

the Brahmaputra to follow their original courses. The Indus flows west until

it rounds the Himalaya by the Nanga Parbat Massif, while the Brahmaputra

flows eastwards for nearly 1000-kms around the Assam Himalayas and descends

to the Bay of Bengal.

It was not surprising, therefore, that 19th century geographers experienced

formidable difficulties n tracing the River systems, and defining the

various mountain ranges that constitute the Himalaya. Even today, with the

advent of satellite pictures and state-of-the-art ordnace maps, it is still

difficult to appreciate the form and extent of some of the ranges that

constitute the Himalaya.

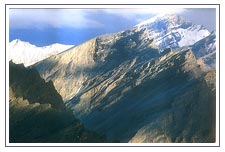

This

is the principal Himalayan mountain range dividing the Indian subcontinent from Nanga

Parbat in the west, the range stretches for over 2,000-km to the mountains

bordering Sikkim and Bhutan in the east. The west Himalaya is the part of

this range that divides Kashmir and Himachal Pradesh from Ladakh. The

highest mountains here are Nun and Kun. In Kashmir the subsidiary ridges of

the Himalaya include the North Sonarmarg, Kolahoi and Amarnath ranges.

Further east, the Himalaya extends across to the Baralacha range in

Himachal Pradesh before merging with the Parbati range to the east of the

Kullu valley. It then extends across kinnaur Kailas to the swargarohini and

Bandarpunch ranges in Uttaranchal. Further east it is defined by the snow

capped range North of the Gangotri glacier and by the huge peaks in the

vicinity of Nanda Devi, the highest mountain in the Indian Himalaya. In

Western Nepal the range is equally prominent across the Annapurna and

Dhaulagiri massifs, while in Eastern Nepal the main ridgeline frequently

coincides with the political boundary between Nepal and Tibet.

The

major passes over the main Himalaya range include the Zoji la, at the head

of the Sindh valley; the Boktol pass, at the head of the Warvan valley; the

Umasi la in the Kishtwar region; and Thekang la and the Shingo la between

Lahaul and the Zanskar region of Ladakh. It also includes the Pin Parbati

pass between Lahaul and the Zanskar region of Ladakh. It also includes the

Pin Parbati pass between the Kullu valley and Spiti, while in Kinnaur it is

traversed when crossing the charang la in the Kinnaur Kailash range.

In Uttaranchal, roads are being constructed to the main places of

pilgrimage in the heart of the Himalaya. These include Yamunotri and the

source of the Yamuna River, Gangotri at the head of the Bhagirathi valley,

Kedarnath at the head of the Mandakini valley, and Badrinath in the

Alaknanda valley. There are, however, many trekking possibilities across the

mountain ridges and glacial valleys including tose bordering the Nanda Devi

sanctuary.

The main Himalaya range extends east across central Sikkim from the huge

Kangchenjunga massif, which includes Kangchenjunga I, the world's third

highest peak. The east Himalaya is breached by the headwaters of the Tista

River, which forms the geographical divide between the verdant alpine

valleys to the south and the more arid regions that extend North to Tibet.

Trekking possibilities are at present confined to the vicinity of the

Singali ridge, an impressive range that exxtends south from the main

Himalayan mountain range and forms the border between India and Nepal.

In Darjeeling the treks include the route along the southern extremity of

the Singali range, while in Sikkim the trails out of Yuksom explore the

ridges and valleys to the south to the Kangchenjunga massif.

The

Pir Panjal Range lies south of the main Himalaya at an average elevation of

5,000m. From Gulmarg in the North west it follows the southern rim of the

Kashmir valley to the Banihal pass. Here the Pir Panjal meets the ridgeline

separating the Kashmir valley from the Warvan valley. From Banihal the Pir

Panjal sweeps south-east to Kishtwar, where the combined waters of the

Warvan and Chandra Rivers meet to form the Chenab River, one of the main

tributaries of the Indus.

Passes In Pir Panjal

The main passes over the Pir Panjal include the pir panjal pass due west of

Srinagar, the Banihal pass which lies at the head of the Jhelum River at the

southern end of the Kashmir valley, and the sythen pass linking Kashmir with

Kishtwar. In Himachal Pradesh the main passes are the Sach which links the

Ravi and the Chandra valleys, and the Rohtang, which links the Beas and

Kullu valleys with the upper Chandra valley and Lahaul. Roads are

constructed over all these passes.

The Banihal is now tunnelled and another road has been made over the Sythen

pass in Kashmir and the Sach pass in Himachal Pradesh. For trekkers there is

still the attraction of the Kugti, Kalicho and Chobia passes between the

Ravi valley and Lahaul, and the Hampta pass links the Kullu valley with

Lahaul.

The

Dhaula Dhar range lies to the south of the Pir Panjal. It is easily

recognised as the snow-capped ridge behind Dharamsala where it forms the

divide between the Ravi and the Beas valleys. To the west it provides the

divide between the Chenab valley below Kishtwar and the Tawi valley which

twists south to Jammu. This is the range crossed at Patnitop on the

Jammu-Srinagar highway. To the east it extends across Himachal Pradesh

forming the high ridges of the Largi gorge and extending south of the Pin

Parvati valley before forming the impressive ridgeline east of the Sutlej

River. Thereon it forms the snow capped divide between the Sangla valley and

upper tons catchment area in Uttaranchal, including the Har Ki Dun Valley.

Beyond the Bhagirathi River it forms the range between Gangotri and

Kedarnath before merging with the main Himalaya at the head of the Gangotri

glacier.

There are many attractive trekking pases over the Dhaula Dhar. These

include the Indrahar Pass North of Dharamsala: and in Kinnaur, the Borasu

pass linking the Sangla valley to Har-ki-Dun in Uttaranchal.

The Siwalik Hills, also known as Shiwalik Hills, lie to

the south of the Dhaula Dhar, with an average elevation of 1,500 to 2,000m.

They are the first range of hills encountered en route from the plains and

are geologically separate from the Himalaya. They include the Jammu hills

and Vaishno Devi, and extend to Kangra and further east to the range south

of Mandi. In Uttaranchal , they extend from Dehra Dun to Almora before

heading across the southern borders of Nepal. Most of the range is crossed

by a network of roads, linking the Northern Indian plains with Kangra, the

Kullu valley, Shimla and Dehradun.

The

Zanskar range lies to the North of the main Himalayan Mountain range. It forms the backbone

of Ladakh south of the Indus River, stretching from the ridges beyond

Lamayuru in the west across the Zanskar region, where it is divided from the

main Himalaya by the Stod and Tsarap valleys, the populated districts of the

Zanskar valley. The Zanskar range is breached where the Zanskar River flows

North, creating awesome gorges until it reaches the Indus River just below

Leh.

To the east of the Zanskar region the range continues through Lahaul &

Spiti, providing a complex buffer zone between the main Himalaya and the

Tibetan plateau. It continues across the North of Kinnaur before extending

west across Uttaranchal, where it again forms the intermediary range between

the Himalaya and the Tibetan plateau, which includes Kamet, the second

highest peak in India. The range finally peters out North east of the Kali

River - close to the border between India and Nepal.

On the Zanskar range, the Fatu La, on the Leh-Srinagar road, is considered

the most easterly pass; while the Singge La, the Cha Cha La and the Rubrang

La are the main trekking passes into the Zanskar valley. For the hardy

Ladakh trader, the main route in winter between the Zanskar valley and Leh

is down the icebound Zanskar River gorges. Further to the east, many of the

Zanskar range passes to the North of Spiti and Kinnaur are close to the

India-Tibet border, and are closed to Trekkers

The ladakh range lies to the North of Leh and is an

integral part of the Trans-Himalayan range that merges with the Kailash

range in Tibet. The passes include the famous Kardung La, the highest

motorable pass in the world, while the Digar La to the North east of Leh is

at present the only pass open to trekkers..

The East Karakoram Range is the huge range that

forms the geographical divide between India and Central Asia. It includes

many high peaks including - Teram Kargri, Saltoro Kangri and Rimo, while the

Karakoram Pass was the main trading link between the markets of Leh, Yarkand

and Kashgar. At present this region is closed to trekkers, although a few

foreign mountaineering groups were permitted to climb there in the last

decade.

It

was a collision that formed mountain ranges right across asia, including the

karakoram, the pamirs, the Hindukush, the Tien Shan and the Kun Lun. The

Himalayan mountains, at the front of this continental collision, are still

being formed, rising and assuming complex profiles. For the ancient

geographer, the complexities of this vast mountain range were a constant

source of speculation. From the earliest accounts, Mt. Kailash was believed

to be the centre of the universe with the River systems of the Indus, the

Brahmaputra, and the Sutlej all flowing from its snowy ridges and

maintaining the courses which they had followed prior to the forming of the

Himalaya.

It

was a collision that formed mountain ranges right across asia, including the

karakoram, the pamirs, the Hindukush, the Tien Shan and the Kun Lun. The

Himalayan mountains, at the front of this continental collision, are still

being formed, rising and assuming complex profiles. For the ancient

geographer, the complexities of this vast mountain range were a constant

source of speculation. From the earliest accounts, Mt. Kailash was believed

to be the centre of the universe with the River systems of the Indus, the

Brahmaputra, and the Sutlej all flowing from its snowy ridges and

maintaining the courses which they had followed prior to the forming of the

Himalaya. This

is the principal Himalayan mountain range dividing the Indian subcontinent from Nanga

Parbat in the west, the range stretches for over 2,000-km to the mountains

bordering Sikkim and Bhutan in the east. The west Himalaya is the part of

this range that divides Kashmir and Himachal Pradesh from Ladakh. The

highest mountains here are Nun and Kun. In Kashmir the subsidiary ridges of

the Himalaya include the North Sonarmarg, Kolahoi and Amarnath ranges.

This

is the principal Himalayan mountain range dividing the Indian subcontinent from Nanga

Parbat in the west, the range stretches for over 2,000-km to the mountains

bordering Sikkim and Bhutan in the east. The west Himalaya is the part of

this range that divides Kashmir and Himachal Pradesh from Ladakh. The

highest mountains here are Nun and Kun. In Kashmir the subsidiary ridges of

the Himalaya include the North Sonarmarg, Kolahoi and Amarnath ranges.  The

major passes over the main Himalaya range include the Zoji la, at the head

of the Sindh valley; the Boktol pass, at the head of the Warvan valley; the

Umasi la in the Kishtwar region; and Thekang la and the Shingo la between

Lahaul and the Zanskar region of Ladakh. It also includes the Pin Parbati

pass between Lahaul and the Zanskar region of Ladakh. It also includes the

Pin Parbati pass between the Kullu valley and Spiti, while in Kinnaur it is

traversed when crossing the charang la in the Kinnaur Kailash range.

The

major passes over the main Himalaya range include the Zoji la, at the head

of the Sindh valley; the Boktol pass, at the head of the Warvan valley; the

Umasi la in the Kishtwar region; and Thekang la and the Shingo la between

Lahaul and the Zanskar region of Ladakh. It also includes the Pin Parbati

pass between Lahaul and the Zanskar region of Ladakh. It also includes the

Pin Parbati pass between the Kullu valley and Spiti, while in Kinnaur it is

traversed when crossing the charang la in the Kinnaur Kailash range. The

Pir Panjal Range lies south of the main Himalaya at an average elevation of

5,000m. From Gulmarg in the North west it follows the southern rim of the

Kashmir valley to the Banihal pass. Here the Pir Panjal meets the ridgeline

separating the Kashmir valley from the Warvan valley. From Banihal the Pir

Panjal sweeps south-east to Kishtwar, where the combined waters of the

Warvan and Chandra Rivers meet to form the Chenab River, one of the main

tributaries of the Indus.

The

Pir Panjal Range lies south of the main Himalaya at an average elevation of

5,000m. From Gulmarg in the North west it follows the southern rim of the

Kashmir valley to the Banihal pass. Here the Pir Panjal meets the ridgeline

separating the Kashmir valley from the Warvan valley. From Banihal the Pir

Panjal sweeps south-east to Kishtwar, where the combined waters of the

Warvan and Chandra Rivers meet to form the Chenab River, one of the main

tributaries of the Indus. The

Dhaula Dhar range lies to the south of the Pir Panjal. It is easily

recognised as the snow-capped ridge behind Dharamsala where it forms the

divide between the Ravi and the Beas valleys. To the west it provides the

divide between the Chenab valley below Kishtwar and the Tawi valley which

twists south to Jammu. This is the range crossed at Patnitop on the

Jammu-Srinagar highway. To the east it extends across Himachal Pradesh

forming the high ridges of the Largi gorge and extending south of the Pin

Parvati valley before forming the impressive ridgeline east of the Sutlej

River. Thereon it forms the snow capped divide between the Sangla valley and

upper tons catchment area in Uttaranchal, including the Har Ki Dun Valley.

Beyond the Bhagirathi River it forms the range between Gangotri and

Kedarnath before merging with the main Himalaya at the head of the Gangotri

glacier.

The

Dhaula Dhar range lies to the south of the Pir Panjal. It is easily

recognised as the snow-capped ridge behind Dharamsala where it forms the

divide between the Ravi and the Beas valleys. To the west it provides the

divide between the Chenab valley below Kishtwar and the Tawi valley which

twists south to Jammu. This is the range crossed at Patnitop on the

Jammu-Srinagar highway. To the east it extends across Himachal Pradesh

forming the high ridges of the Largi gorge and extending south of the Pin

Parvati valley before forming the impressive ridgeline east of the Sutlej

River. Thereon it forms the snow capped divide between the Sangla valley and

upper tons catchment area in Uttaranchal, including the Har Ki Dun Valley.

Beyond the Bhagirathi River it forms the range between Gangotri and

Kedarnath before merging with the main Himalaya at the head of the Gangotri

glacier. The

Zanskar range lies to the North of the main Himalayan Mountain range. It forms the backbone

of Ladakh south of the Indus River, stretching from the ridges beyond

Lamayuru in the west across the Zanskar region, where it is divided from the

main Himalaya by the Stod and Tsarap valleys, the populated districts of the

Zanskar valley. The Zanskar range is breached where the Zanskar River flows

North, creating awesome gorges until it reaches the Indus River just below

Leh.

The

Zanskar range lies to the North of the main Himalayan Mountain range. It forms the backbone

of Ladakh south of the Indus River, stretching from the ridges beyond

Lamayuru in the west across the Zanskar region, where it is divided from the

main Himalaya by the Stod and Tsarap valleys, the populated districts of the

Zanskar valley. The Zanskar range is breached where the Zanskar River flows

North, creating awesome gorges until it reaches the Indus River just below

Leh.